Lindsay Perryman’s ‘Tops’ places Black transmasculinity in the photographic canon

"It’s just very crucial to me that these images can be looked at by the next generation, and for people to be welcomed and not othered.”

"It’s just very crucial to me that these images can be looked at by the next generation, and for people to be welcomed and not othered.”

Words by Jess Cole

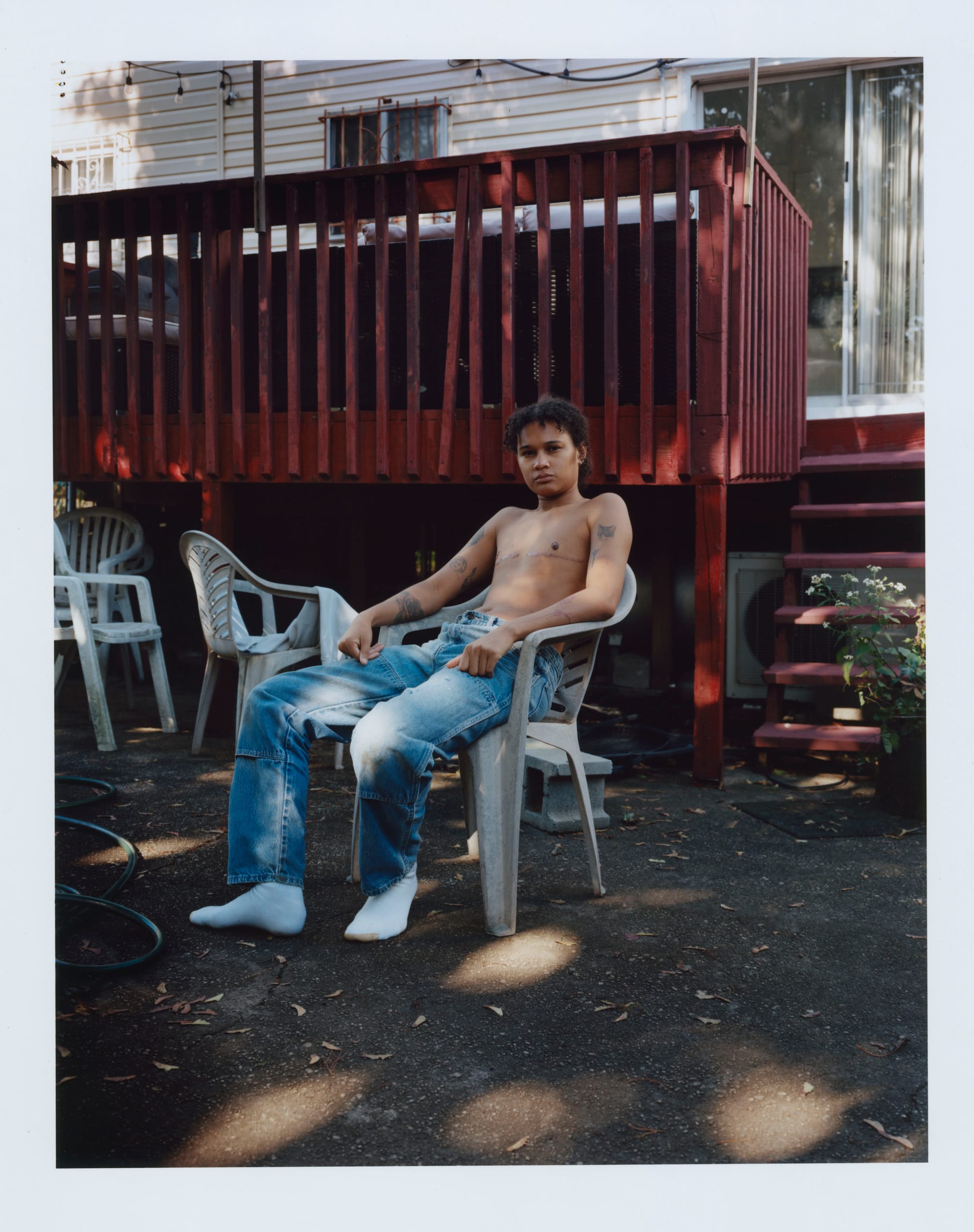

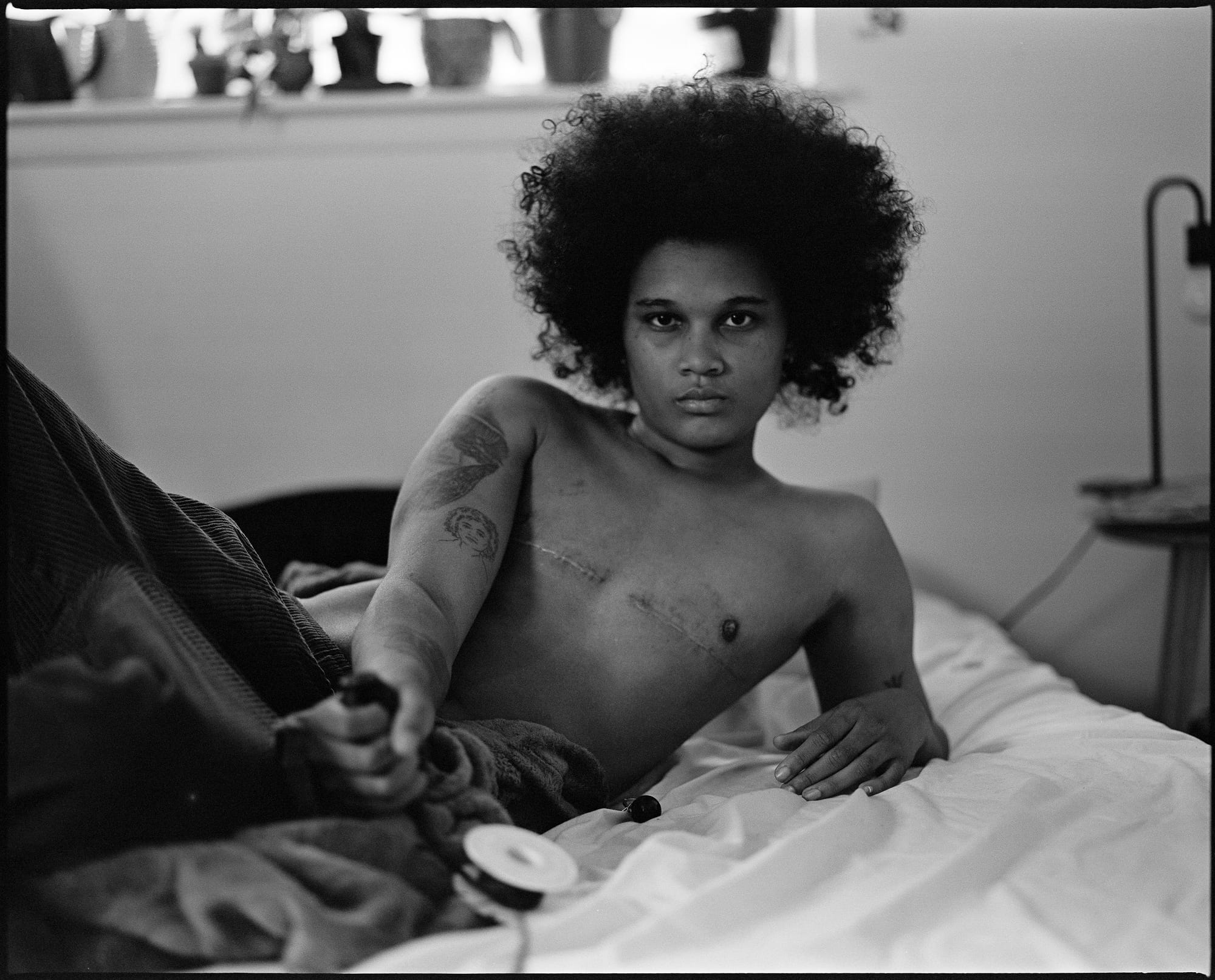

A shimmer of Brown torsos appear one after another. Some stand still, others cross their arms, some shift their weight from side to side. Each body is for a moment, anonymous, their heads just out of frame. The afternoon light cascades across each person, contouring the surgery scars that run along their chest wall. The camera lingers, but doesn’t fixate. The background is softly soundtracked by the strums of a guitar. A voice overlaps and echoes into a collective reflection on top surgery. The view then peels away to reveal the faces behind the swirling audible narratives. Shot in 2024, Lindsay Perryman’s short film, ‘Tops’, is a visual mediation on the often overlooked experiences of Black transmasculinity.

Lindsay Perryman is a photographer and a non-binary trans person, whose work has been showcased at the likes of The Brooklyn museum, awarded the 2024 Palm Photo prize, and collected in the permanent collection of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. As we chat over Zoom, Lindsay, who is a born-and-raised Brooklyner, credits New York City as opening them up to the eclecticism of people and cultures, which have become touchstones in grounding their work between the personal and universal. They grew up in an artistic household in what they affectionately refer to as the “suburbia of Canarsie”, and reflected on how there had always been an element of photography in their family. “I think photos are important to most Black households really, there’s always a photobook lying around”, Lindsay tells me.

Indeed, Black studio photographers have historically played a huge role in reclaiming identities that have been mired in racist depictions. A point that catalysed Lindsay’s use of the medium to create an archive of Black queerness, especially of Black trans people, who are still glaringly absent from the photographic cannon. “It’s just very crucial to me that these images can be looked at by the next generation, and for people to be welcomed and not othered”, Lindsay comments. An ethos which puts their work in lineage with the Black family portraiture of Carrie Mae Weems, and feels connected in part, to the work of the black South African photographer Zanele Muholi, who documents South Africa’s Black queer communities.

“I really wanted to capture the community aspect of just like, aftercare. It's such a beautiful image, action, thought, to have someone put the gel on you, and say I want to take care of you.”

For Lindsay, their work is heavily guided by their own experiences of identity and sexuality. During the pandemic, they created ‘The Colors We Don’t See at The End of The Rainbow’, which was a celebration of the Black and Brown studs of the LGBTQIA+ community. “It’s funny because that’s how I identified at the time, and then as the years went on I finally figured out who I was, and my work is reflective of that”, Lindsay remarks, “I had top surgery in 2021, so ‘Tops’ was borne from a desire to explore the intimacy and vulnerability that comes with undergoing surgery”.

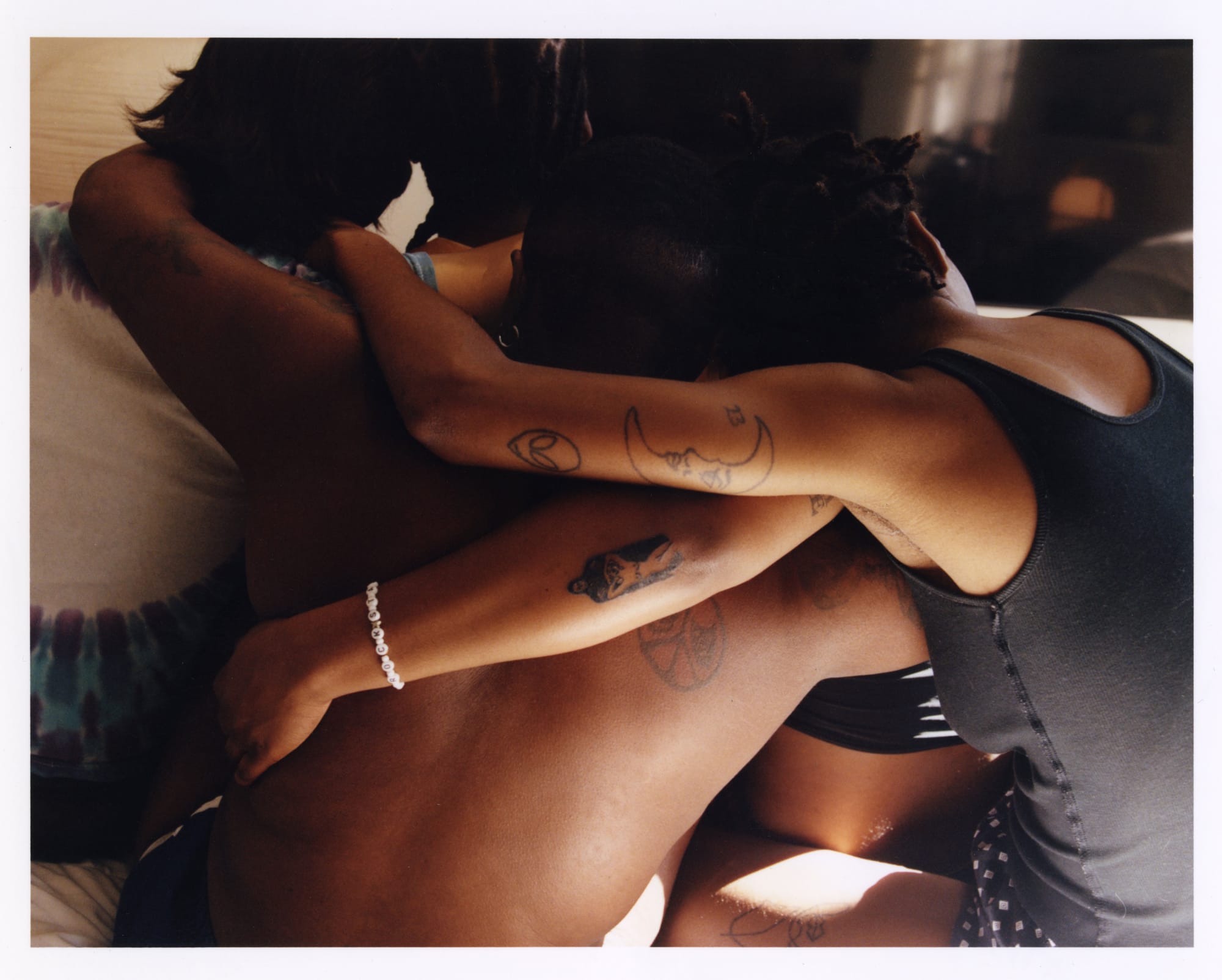

Staging the film in their mom’s home, Lindsay conveys a sense of comfort and of ease for Black transmasculinity that so rarely gets the space, publicly, to heal and to reflect. Indeed there are moments of total idleness, where the models simply lounge on one another. It reminds me of the Black utopic dreamscapes of Tyler Mitchell’s photography. A softening moment, of transness, of Blackness not having to explain or define, or do or defend or fight, but simply just be. It’s the romanticising of what can be often a complicated and painful process, that Lindsay says stems from the overwhelming sense of love they received and felt, after their post-op surgery. “It was a time where I was totally reliant on my family, and I felt the most loved during that time”, Lindsay recalls. “My Dad flew in from Atlanta to be with me. It was honestly a pivotal moment in my life”

Shot on a Super 8 camera, Lindsay captures the poetry of caregiving and receiving care. A particularly poignant scene is of the models Zaire and Blaze, topless and entwined on a bed, rubbing healing gel into each other’s post-op scars. “I really wanted to capture the community aspect of just like, aftercare,” Lindsay remarks. “I think it’s such a beautiful image, action, thought, to have someone put the gel on you, and say I want to take care of you.” It also permeates into a sense of empowerment, and a sense of hope, that it is fundamentally a right, to have and retain autonomy of choice in medical procedures and one’s choices of care.

Perhaps somewhat, controversially, Lindsay doesn’t shy away from the prominence of the surgery scars on each of the models. There is of course an ongoing debate, as to the visibility of surgery scars, and how their use, particularly in fashion or even Costa Coffee campaigns can do more damage than good. Those opposed argue the dangers of over exposing transmasculinity, without offering any defense from a virulent medial, or immediately backtracking, after a campaign backlash. See: Campbell King, Burberry campaign. Especially given the current toxic political climate, and stats which reveal trans people are four times more likely to be abused than cis people. However, for Lindsay and their work, scars are a way of “ honouring the body’s history and the narratives it carries”. They are evidence of survival, transformation,” Lindsay muses. “They represent not just physical change, but emotional and communal healing.”

A healing that Lindsay celebrates, but also ponders the difficulties of, in the still photographs that are evolving ‘Tops’ into a photographic series. In one shot we see Adair, shirtless and resplendent, on a sofa with huge feathered angel wings. A caged bird yearning to be free, or perhaps a person that has finally been given their wings. In another image, we see Euro observing his shape and form in the mirror, a quiet contemplation etched onto his brow. It is through the continuation of ‘Tops’, that Lindsay seeks to reflect the fluidity of the process of top surgery, without shying away from the pitfalls that come with it. In the closing credits of their short, Lindsay reflects on the experience of seeing themselves unbandaged: “I knew it was what I wanted, but I wasn’t sure how to feel. I was grieving. Although I was quite relieved”.

In being so open about the feeling of loss, and at the same time experiencing the feeling of gain. Lindsay speaks on what they so elegantly capture in their images: The knotty complexities and contradictions, loves and losses that texturise and give weight to life, and lives that are not minimised by our gender, or our race, but lived and are living in all of our moments of contemplation and chaos, thoughts and frivolity.